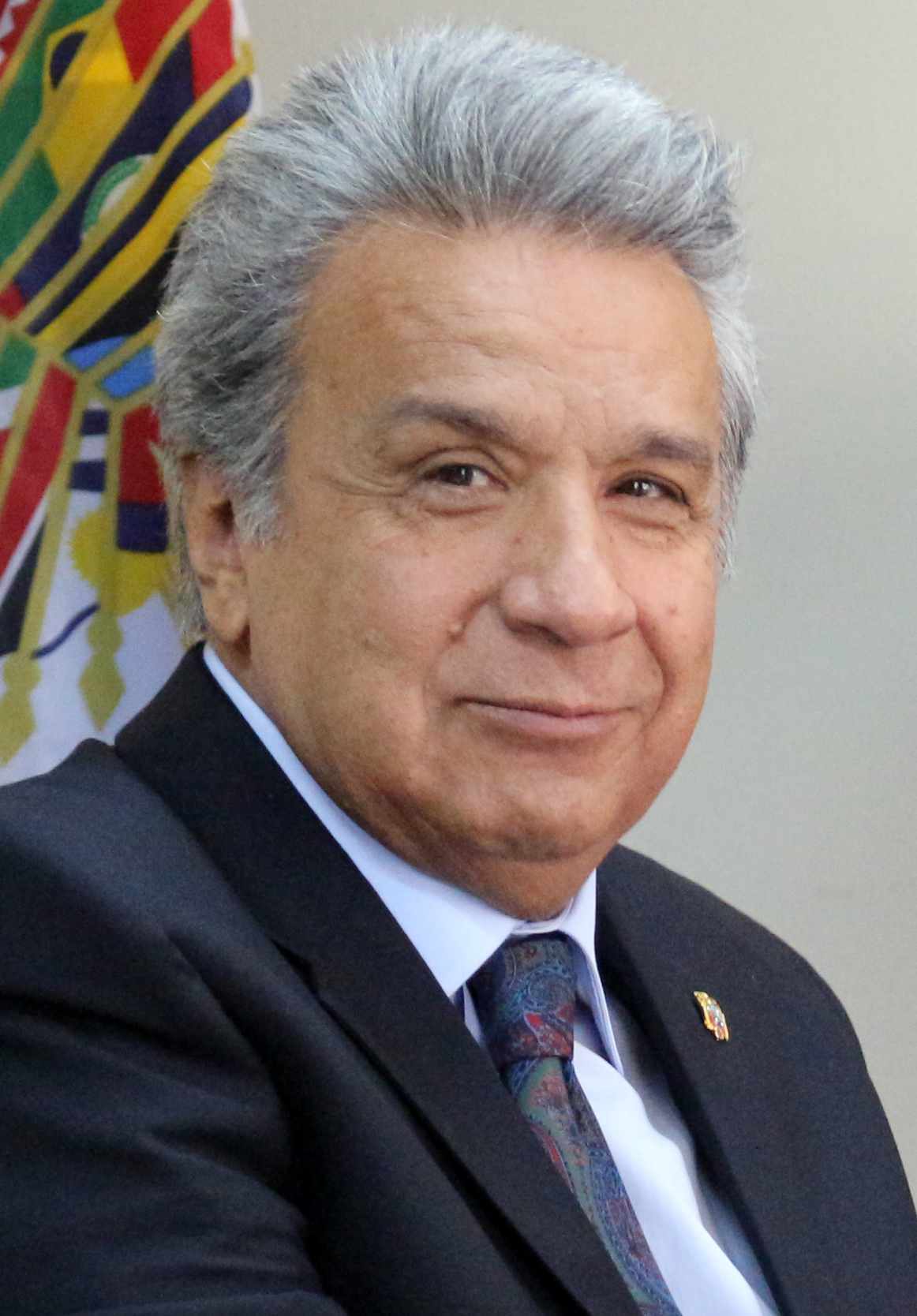

Former Ecuadorian President Lenín Moreno to Stand Trial in “Sinohydro China Case”

Former Ecuadorian President Lenín Moreno (2017-2021) will stand trial for alleged bribery in the well-known “Sinohydro case,” which refers to the Chinese company responsible for building the country’s largest hydroelectric plant while he served as vice president under Rafael Correa (2007-2017).

After determining that sufficient elements exist to presume Moreno’s participation in the crime of bribery, the judge ruled on Monday to call him to trial during a hearing in which the decision regarding 23 other individuals is also expected.

As an alternative measure to pre-trial detention, the judge ordered Moreno to appear twice a month at the Ecuadorian Embassy in Asunción (Paraguay), where he currently resides with his wife.

Last Thursday, Moreno reiterated that the criminal proceedings against him for alleged bribes received while he was vice president constitute “revenge” by Correísmo for his rebellion once he became president, which, in his view, prevented Ecuador from becoming “a perpetual dictatorship and turning into another Venezuela.”

Moreno’s defense

The Prosecutor’s Office maintains that, while Moreno was Correa’s vice president, he and his family allegedly received more than one million dollars in bribes from the Chinese state-owned company Sinohydro in connection with the construction of the Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric plant, the largest in the country.

In a video message posted on social media, Moreno asserted that it “has not been possible to prove” that he “received a single cent,” and he also defended the innocence of his wife and daughter, who are likewise being prosecuted.

“Who awarded the contract? Rafael Correa Delgado. Who arranged the financing and executed the work? (Former minister and former vice president) Jorge Glas,” he pointed out, questioning “why Rafael Correa, Jorge Glas, and the ministers and officials of that era are not part of the proceedings.”

Moreno stressed that the plant was inaugurated “in November 2016 in the presence of Rafael Correa and Jorge Glas, and at that time the works were not inspected and, irresponsibly, more than 100 million dollars in guarantees were returned.”

“When I became president, we detected more than 17,000 cracks in the project, which is why I refused to accept it and immediately initiated arbitration proceedings,” emphasized Moreno, who currently serves in Paraguay as the OAS Commissioner for Disability Affairs.

The case

The Prosecutor’s Office believes that the total bribes paid by Sinohydro in the Coca Codo Sinclair project allegedly exceed 76 million dollars.

The case broke in 2019 when the investigative journalism outlet La Fuente published a report linking one of Moreno’s brothers to alleged offshore accounts and a luxury property in Alicante (Spain) through an apparent triangulation involving an opaque company.

That journalistic investigation revealed a series of connections and alleged irregularities that apparently tied Moreno to the offshore company INA Investment, prompting an initial investigation by the Prosecutor’s Office. According to the prosecution, Moreno allegedly received US$660,000 unlawfully, of which US$220,000 were allegedly destined for him and his wife (supposedly in the form of an apartment and furniture). The remaining US$440,000 were allegedly distributed to his brothers Edwin (US$350,000) and Guillermo (US$10,000), his daughter Irina (US$50,000), and his sisters-in-law Jacqueline (US$10,000).

ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance)

From a strictly ESG perspective and based only on undisputed or officially documented facts (not on unproven allegations in the ongoing criminal case), the Coca Codo Sinclair project and the broader Sinohydro case raise several serious and well-documented ESG concerns:

Environmental (E)

The Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric plant (1,500 MW), despite being presented as renewable energy infrastructure, has been plagued by severe construction defects. Official technical reports and the arbitration process initiated by the Ecuadorian State (2018–present) before the International Chamber of Commerce have confirmed the existence of thousands of cracks in the distributors, serious erosion problems in the Coca River catchment area, and sediment management failures.

These defects have reduced the plant’s effective generation capacity well below design parameters and increased the risk of catastrophic failure, with potential downstream impacts on ecosystems and communities.

The project has also been criticized by the Comptroller General of Ecuador and independent engineering audits for inadequate environmental impact studies and for being built in a geologically high-risk zone prone to seismic activity and erosion.

Social (S)

Thousands of families along the Coca River have been affected by regression of the San Rafael waterfall (2020 collapse, widely attributed to the plant’s alteration of the river’s flow regime) and by ongoing erosion that threatens roads, bridges, and oil infrastructure.

Local communities have reported loss of tourism income and fishing resources, as well as increased vulnerability to flooding.

Governance (G)

Regardless of the final outcome of the criminal proceedings, the project exemplifies long-standing governance failures in Ecuador’s public procurement and oversight of mega-infrastructure projects:

Lack of competitive international bidding (the contract was awarded directly to Sinohydro).

Weak technical supervision during construction under the Correa administration.

Premature return of more than US$100 million in performance bonds before full acceptance of the works (documented by the Comptroller General).

The case has exposed systemic risks in contracts with foreign state-owned enterprises in which large credit lines from the financier (in this case China Eximbank) are tied to the mandatory awarding of the contract to a specific contractor, reducing transparency and competition.

In summary, even setting aside the bribery allegations still under judicial investigation, the Coca Codo Sinclair project constitutes a textbook example of poor ESG risk management in a major infrastructure project: environmental and technical shortcomings with long-term consequences, negative social impacts on local populations, and clear governance failures in procurement and oversight. These objective deficiencies have already resulted in hundreds of millions of dollars in losses and reparations claimed by Ecuador in international arbitration.